I’ve been on a web tweaking kick lately: how to speed up your javascript, gzip files with your server, and now how to set up caching. But the reason is simple: site performance is a feature.

For web sites, speed may be feature #1. Users hate waiting, we get frustrated by buffering videos and pages that pop together as images slowly load. It’s a jarring (aka bad) user experience. Time invested in site optimization is well worth it, so let’s dive in.

What is Caching?

Caching is a great example of the ubiquitous time-space tradeoff in programming. You can save time by using space to store results.

In the case of websites, the browser can save a copy of images, stylesheets, javascript or the entire page. The next time the user needs that resource (such as a script or logo that appears on every page), the browser doesn’t have to download it again. Fewer downloads means a faster, happier site.

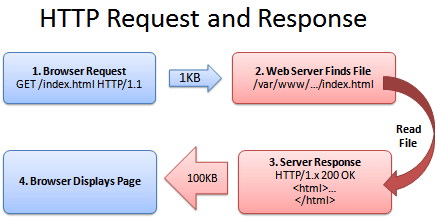

Here’s a quick refresher on how a web browser gets a page from the server:

1. Browser: Yo! You got index.html?

2. Server: (Looking it up…)

3. Sever: Totally, dude! It’s right here!

4. Browser: That’s rad, I’m downloading it now and showing the user.

(The actual HTTP protocol may have minor differences; see Live HTTP Headers for more details.)

Caching’s Ugly Secret: It Gets Stale

Caching seems fun and easy. The browser saves a copy of a file (like a logo image) and uses this cached (saved) copy on each page that needs the logo. This avoids having to download the image ever again and is perfect, right?

Wrongo. What happens when the company logo changes? Amazon.com becomes Nile.com? Google becomes Quadrillion?

We’ve got a problem. The shiny new logo needs to go with the shiny new site, caches be damned.

So even though the browser has the logo, it doesn’t know whether the image can be used. After all, the file may have changed on the server and there could be an updated version.

So why bother caching if we can’t be sure if the file is good? Luckily, there’s a few ways to fix this problem.

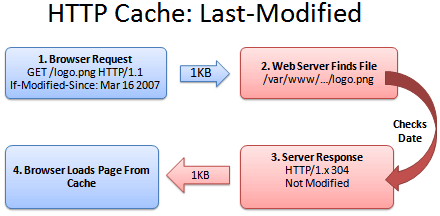

Caching Method 1: Last-Modified

One fix is for the server to tell the browser what version of the file it is sending. A server can return a Last-modified date along with the file (let’s call it logo.png), like this:

Last-modified: Fri, 16 Mar 2007 04:00:25 GMT

File Contents (could be an image, HTML, CSS, Javascript...)

Now the browser knows that the file it got (logo.png) was created on Mar 16 2007. The next time the browser needs logo.png, it can do a special check with the server:

1. Browser: Hey, give me logo.png, but only if it’s been modified since Mar 16, 2007.

2. Server: (Checking the modification date)

3. Server: Hey, you’re in luck! It was not modified since that date. You have the latest version.

4. Browser: Great! I’ll show the user the cached version.

Sending the short “Not Modified†message is a lot faster than needing to download the file again, especially for giant javascript or image files. Caching saves the day (err… the bandwidth).

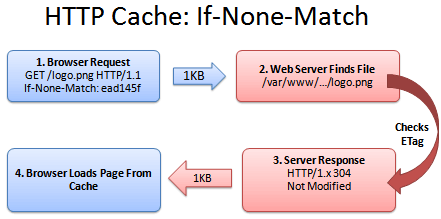

Caching Method 2: ETag

Comparing versions with the modification time generally works, but could lead to problems. What if the server’s clock was originally wrong and then got fixed? What if daylight savings time comes early and the server isn’t updated? The caches could be inaccurate.

ETags to the rescue. An ETag is a unique identifier given to every file. It’s like a hash or fingerprint: every file gets a unique fingerprint, and if you change the file (even by one byte), the fingerprint changes as well.

Instead of sending back the modification time, the server can send back the ETag (fingerprint):

ETag: ead145f

File Contents (could be an image, HTML, CSS, Javascript...)

The ETag can be any string which uniquely identifies the file. The next time the browser needs logo.png, it can have a conversation like this:

1. Browser: Can I get logo.png, if nothing matches tag “ead145f�

2. Server: (Checking fingerprint on logo.png)

3. Server: You’re in luck! The version here is “ead145fâ€. It was not modified.

4. Browser: Score! I’ll show the user my cached version.

Just like last-modifed, ETags solve the problem of comparing file versions, except that “if-none-match†is a bit harder to work into a sentence than “if-modified-sinceâ€. But that’s my problem, not yours. ETags work great.

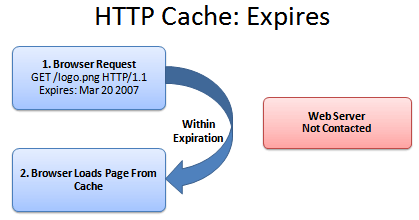

Caching Method 3: Expires

Caching a file and checking with the server is nice, except for one thing: we are still checking with the server. It’s like analyzing your milk every time you make cereal to see whether it’s safe to drink. Sure, it’s better than buying a new gallon each time, but it’s not exactly wonderful.

And how do we handle this milk situation? With an expiration date!

If we know when the milk (logo.png) expires, we keep using it until that date (and maybe a few days longer, if you’re a college student). As soon as it goes expires, we contact the server for a fresh copy, with a new expiration date. The header looks like this:

Expires: Tue, 20 Mar 2007 04:00:25 GMT

File Contents (could be an image, HTML, CSS, Javascript...)

In the meantime, we avoid even talking to the server if we’re in the expiration period:

There isn’t a conversation here; the browser has a monologue.

1. Browser: Self, is it before the expiration date of Mar 20, 2007? (Assume it is).

2. Browser: Verily, I will show the user the cached version.

And that’s that. The web server didn’t have to do anything. The user sees the file instantly.

Caching Method 4: Max-Age

Oh, we’re not done yet. Expires is great, but it has to be computed for every date. The max-age header lets us say “This file expires 1 week from todayâ€, which is simpler than setting an explicit date.

Max-Age is measured in seconds. Here’s a few quick second conversions:

- 1 day in seconds = 86400

- 1 week in seconds = 604800

- 1 month in seconds = 2629000

- 1 year in seconds = 31536000 (effectively infinite on internet time)

Bonus Header: Public and Private

The cache headers never cease. Sometimes a server needs to control when certain resources are cached.

Cache-control: publicmeans the cached version can be saved by proxies and other intermediate servers, where everyone can see it.Cache-control: privatemeans the file is different for different users (such as their personal homepage). The user’s private browser can cache it, but not public proxies.Cache-control: no-cachemeans the file should not be cached. This is useful for things like search results where the URL appears the same but the content may change.

However, be wary that some cache directives only work on newer HTTP 1.1 browsers. If you are doing special caching of authenticated pages then read more about caching.

Ok, I’m Sold: Enable Caching

First, make sure Apache has mod_headers and mod_expires enabled:

... list your current modules...

apachectl -t -D DUMP_MODULES

... enable headers and expires if not in the list above...

a2enmod headers

a2enmod expires

The general format for setting headers is

- File types to match

- Header / Expiration to set

A general tip: the less a resource changes (images, pdfs, etc.) the longer you should cache it. If it never changes (every version has a different URL) then cache it for as long as you can (i.e. a year)!

One technique: Have a loader file (index.html) which is not cached, but that knows the locations of the items which are cached permanently. The user will always get the loader file, but may have already cached the resources it points to.

The following config settings are based on the ones at AskApache.

Seconds Calculator

All the times are given in seconds (A0 = Access + 0 seconds).

Using Expires Headers

ExpiresActive On

ExpiresDefault A0

# 1 YEAR - doesn't change often

<FilesMatch "\.(flv|ico|pdf|avi|mov|ppt|doc|mp3|wmv|wav)$">

ExpiresDefault A29030400

</FilesMatch>

# 1 WEEK - possible to be changed, unlikely

<FilesMatch "\.(jpg|jpeg|png|gif|swf)$">

ExpiresDefault A604800

</FilesMatch>

# 3 HOUR - core content, changes quickly

<FilesMatch "\.(txt|xml|js|css)$">

ExpiresDefault A10800

</FilesMatch>

Again, if you know certain content (like javascript) won’t be changing often, have “js†files expire after a week.

Using max-age headers:

# 1 YEAR

<FilesMatch "\.(flv|ico|pdf|avi|mov|ppt|doc|mp3|wmv|wav)$">

Header set Cache-Control "max-age=29030400, public"

</FilesMatch>

# 1 WEEK

<FilesMatch "\.(jpg|jpeg|png|gif|swf)$">

Header set Cache-Control "max-age=604800, public"

</FilesMatch>

# 3 HOUR

<FilesMatch "\.(txt|xml|js|css)$">

Header set Cache-Control "max-age=10800"

</FilesMatch>

# NEVER CACHE - notice the extra directives

<FilesMatch "\.(html|htm|php|cgi|pl)$">

Header set Cache-Control "max-age=0, private, no-store, no-cache, must-revalidate"

</FilesMatch>

Final Step: Check Your Caching

To see whether your files are cached, do the following:

- Online: Examine your site in the cacheability query (green means cacheable)

- In Browser: Use FireBug or Live HTTP Headers to see the HTTP response (304 Not Modified, Cache-Control, etc.). In particular, I’ll load a page and use Live HTTP Headers to make sure no packets are being sent to load images, logos, and other cached files. If you press ctrl+refresh the browser will force a reload of all files.

Read more about caching, or the HTTP header fields. Caching doesn’t help with the initial download (that’s what gzip is for), but it makes the overall site experience much better.

Remember: Creating unique URLs is the simplest way to caching heaven. Have fun streamlining your site!

Source:http://betterexplained.com/articles/how-to-optimize-your-site-with-http-caching/